http://bit.ly/1lNab2C has more information

Tag Archives: statins

Cholesterol – look after it!

Low-Cholesterol and Violent Behaviours

2004; 97: 229-35

Cholesterol & Insulin

productive over the long-term.

Good or Bad Lipid Profiles

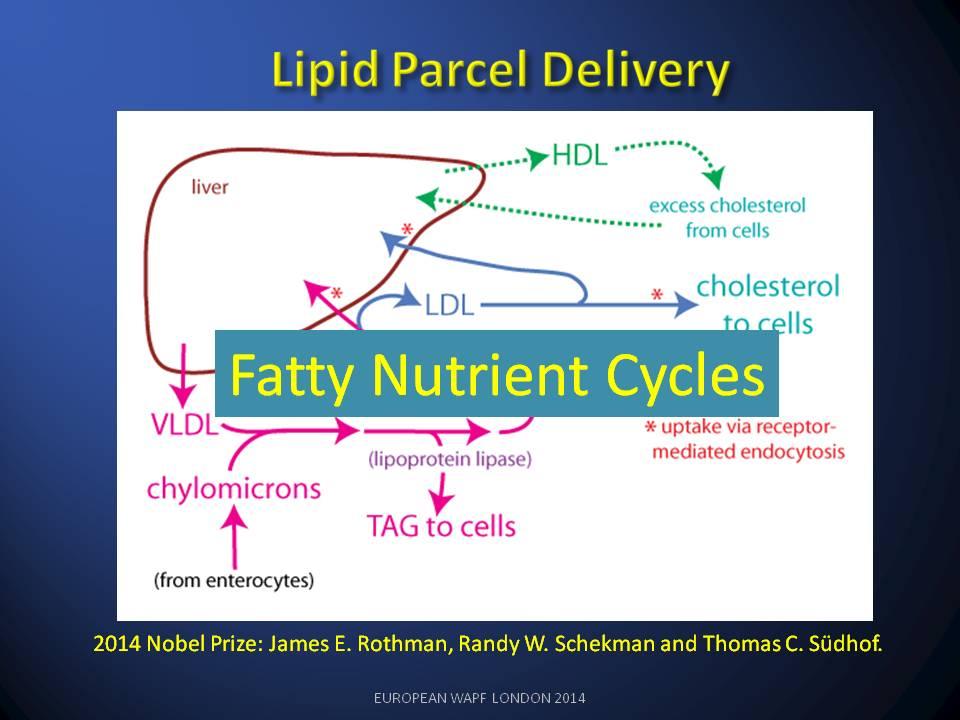

The 2013 Nobel Prize for Medicine raised expectations of a parallel discussion of extra-cellular lipid circulation in The Lipid Cycle. A better understanding of the health problems caused by disruption to The Lipid Cycle has been blocked for over 40 years by incorrect use of the chemical term ‘cholesterol’ as an inaccurate surrogate when referring to Lipid profiles. This singular error has caused decades of misunderstanding and inappropriate treatments in medicine.

The Lipid Cycle

Understand this means it should have better been called ‘Bad-LDL’.

The HDL lipid class operate on the return side of the lipid cycle and is depleted when LDL is damaged.

The High Cholesterol Paradox

Link

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0cm;

mso-para-margin-right:0cm;

mso-para-margin-bottom:10.0pt;

mso-para-margin-left:0cm;

line-height:115%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Thank you Dr Verner Wheelock for the extensive critique of the reports . The Cochrane reports analysis was heroic and well structured. We had a huge debate about them at the time on THINCS (www.thincs.org).

For my part I shy away from statistical analysis which doesn’t include ‘All Cause Mortality’ figures. The reason being that failure to look at all the non-cardio deaths and drop-outs from trials cleans and amplifies the apparent benefits of Statins. This means we can never know the Numbers Needed to Harm NNH side of the medication.

My first ever review paper (G Wainwright et al., 2009) looking at the clinical impact of cholesterol lowering in all non-cardiovascular organs, was seminal in that it pointed up a fundamental flaw in the whole statin concept i.e. Cholesterol is vital and inhibiting its production is destined to create a wide and varied set of Adverse Events in statin users in the longer term. That is why ‘all cause mortality’ data is not made available (caveat emptor).

In our second review paper(Seneff et al., 2011) we became aware of the fact that LDL/HDL ratios were associated with LDL consumption by organs and not production by the liver. The whole LDL argument had been inverted. If LDL is damaged by glycation, LDL goes up and HDL falls. The liver’s glycated-LDL is unused and the corresponding HDL return to the liver does not happen.

How such a fundamental part of the lipid nutrition cycle could be missed is hard to understand. Obsession with statins and statin finance has done immense harm to cardio-medicine and I believe we are seeing the start of a major NICE scandal as the BMA object to the guidance.

Link

Link

Current guidelines encourage ambitious long term cholesterol lowering with statins, in order to decrease cardiovascular disease events. However, by regulating the biosynthesis of cholesterol we potentially change the form and function of every cell membrane from the head to the toe. As research…

Nowhere is the impact of cholesterol depletion more keenly studied than in the neurologic arena.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-GB

X-NONE

X-NONE

MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0cm;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}

Link

Link

As experts clash over proposals that millions more of us take statins to prevent heart disease and stroke, a vascular surgeon explains why he feels better without them

You can also read my related essay on this link http://bit.ly/1fkGYgb